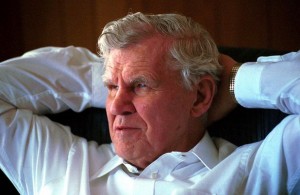

Music legend Doc Watson dies at 89

Grammy-winning U.S. guitarist and folk singer Arthel Lane “Doc” Watson died on Tuesday in a North Carolina hospital at age 89 – his management company said.

Watson died at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center in Winston-Salem, following abdominal surgery last week, Folklore Productions International said in a statement.

“Doc was a legendary performer who blended his traditional Appalachian musical roots with bluegrass, country, gospel and blues to create a unique style and an expansive repertoire” – the statement said. “He was a powerful singer and a tremendously influential picker who virtually invented the art of playing mountain fiddle tunes on the flattop guitar.”

Watson, who was blinded before his first birthday, won seven Grammy Awards, in addition to the Grammy for lifetime achievement he received in 2004. In 2006 he won in the category of best country instrumental performance for his playing on “Whiskey Before Breakfast.”

Watson was born on March 3, 1923, in Deep Gap, North Carolina, to a banjo-playing father, General Watson, and a mother who sang traditional secular and religious songs, Annie Watson.

Blinded by an eye infection as a toddler, he learned to play the banjo first, then taught himself the chords to “When the Roses Bloom in Dixieland” on a borrowed guitar at age 13 – his managers said.

You could hear the mountains of North Carolina in Doc Watson’s music. The rush of a mountain stream, the steady creak of a mule in leather harness plowing rows in topsoil and the echoes of ancient sounds made by a vanishing people were an intrinsic part of the folk musician’s powerful, homespun sound.

It took Watson decades to make a name for himself outside the world of Deep Gap, North Carolina. Once he did, he ignited the imaginations of countless guitar players who learned the possibilities of the instrument from the humble picker who never quite went out of style. From the folk revival of the 1960s to the Americana movement of the 21st century, Watson remained a constant source of inspiration and a treasured touchstone before his death Tuesday at age 89.

Blind from the age of 1, Watson was left to listen to the world around him and it was as if he heard things differently from others. Though he knew how to play the banjo and harmonica from an early age, he came to favour the guitar. His flat-picking style helped translate the fiddle- and mandolin-dominated music of his forebears for an audience of younger listeners who were open to the tales that had echoed off the mountains for generations, and to the new lead role for the guitar.

“Overall, Doc will be remembered as one of America’s greatest folk musicians. I would say he’s one of America’s greatest musicians” – said David Holt, a longtime friend and collaborator who compared Watson to Lead Belly, Bill Monroe, Muddy Waters and Earl Scruggs.

Like those pioneering players, Watson took a regional sound and made it into something larger, a piece of American culture that reverberates for decades after the notes are first played.

“He had a great way of presenting traditional songs and making them accessible to a modern audience” – Holt said. “Not just accessible, but truly engaging.”

Watson was never a big record-seller, making the Billboard charts only once in his career. And then no higher than No. 193, in 1975 with the album “Memories”. But he transcended mainstream popularity, earning eight Grammy Awards, including a lifetime achievement award in 2004.

Watson’s influence was vast, on audiences and other musicians.

“He was a great and groundbreaking guitarist, but Doc was more than that” – said Wayne Martin, executive director of the North Carolina Arts Council. “He made musical traditions of Western North Carolina and the Blue Ridge Mountains accessible to millions. His guitar was a powerful tool to get people’s attention, but I don’t think it was his greatest legacy.”

Watson was instrumental in transforming the guitar from a background rhythm role to a lead instrument in acoustic music. Yet few players in any style came close to duplicating his flawless flatpicking style. Generations of acoustic guitarists would spend hours trying to match the grace and speed Watson combined as he played tunes such as “Black Mountain Rag” and “Billy in the Lowground.”

Watson never went out of his way to call attention to himself. Barry Poss, who released 13 of Watson’s albums on his Sugar Hill Records label, used to get frustrated with Watson’s modesty in the recording studio.

“If there’s another guitar player around, he’ll almost always defer to that other player and lay back” – Poss said of Watson in 2003. “He really has no interest in pretentiousness, showing off, ’Here’s what I can do.’ It just never happens. In the studio, it can be hard to get him to take a hot lead.”

While he played all over the world, Watson still lived most of his life in the vicinity of the Deep Gap community where he was born in 1923. Blind since infancy, Watson’s first childhood instrument was harmonica. His father made him a banjo at age 10, and he learned the basics of guitar from a neighbor.

Watson was always pragmatic about music as a way to make a living. He began playing for money in the 1940′s because, as a blind man, he had few other career options. Jack Lawrence, who played with Watson for more than a quarter-century, frequently said that Watson preferred home to being on the road and was less interested in being remembered for his music than as “the good ol’ boy down the road.”