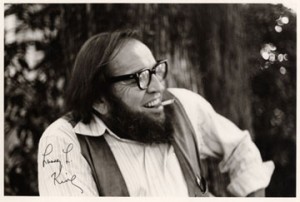

Writer Larry L. King dead at 83

Larry L. King, a journalist, essayist and playwright with a swaggering prose style and a rollicking personal one, who left Texas as a young man but never abandoned it in his work — turning out profiles of politicians, articles on the flaws and foibles of American culture, searching autobiographical essays and, most famously, the book for the Broadway musical “The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas” — died on Thursday in Washington. He was 83.

The cause was emphysema, his wife (Barbara Blaine) said.

A prolific writer for Texas Monthly, Harper’s, Playboy and other magazines, Mr. King had a big personality suffused with humor, characteristics evident in his work. Critics often noted his affinity for the wordplay, wry attitude and joy in the existence of scalawags that were hallmarks of Mark Twain. Nor was he, like Twain, loath to cast aspersions on the dull, the self-righteous and the oafish.

“There are ‘good’ people, yes, who might properly answer to the appellation ‘redneck’ ” – he wrote in Texas Monthly in 1974, “people who operate Mom-and-Pop stores or their lathes, dutifully pay their taxes, lend a helping hand to neighbors, love their country and their God and their dogs. But even among a high percentage of these salts-of-the-earth lives a terrible reluctance toward even modest passes at social justice, a suspicious regard of the mind as an instrument of worth, a view of the world extending little further than the ends of their own noses and only a vague notion that they are small quills writing a large history.”

Larry L. King, a writer and playwright whose magazine article about a campaign to close down a popular bordello became the hit Broadway musical “The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas” and a 1982 movie starring Burt Reynolds, died Thursday. He was 83.

King (who had emphysema) died at a retirement home in Washington, D.C., where he had lived for six months, said his wife, Barbara Blaine.

He wrote his most famous piece, about the demise of the Chicken Ranch brothel in Texas, in 1974 for Playboy magazine. When Peter Masterson, an actor from Texas, came across the article in his Broadway dressing room, he proposed making a musical out of it and persuaded another Texan to get involved, composer Carol Hall.

King was so certain the play would fail that he kept a journal in the hope that “he could whip up its obit notice into a funny magazine piece” – The Times reported in 1980.

Instead the Tommy Tune-directed production became a smash hit after opening on Broadway in 1978, running until 1982. Touring productions were staged around the world.

When asked what made the bawdy musical comedy a success, King had cited the “subject matter and a million-dollar title” — and Tune’s choreography.

The film version starring Reynolds and Dolly Parton was less than a hit with critics, including King, who thought Hollywood had ruined the story and turned it into a sex romp.

A sequel to the play (“The Best Little Whorehouse Goes Public”) by the same creative team flopped on Broadway in 1994.

Though Larry L. King shared a name with a popular radio and TV host, the writer was a singular Texas raconteur who could be confused with no other.

A famed drinker and brawler, King will forever be best known for a 1974 Playboy story about the Chicken Ranch brothel in La Grange, which he helped turn into the hit musical “The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas.”

He spent more than half of his life living in Washington, D.C., but King’s storytelling style always revealed his West Texas roots. One of his editors, the late, great Willie Morris, commented on King’s “deep and abiding commitment to American and to authentic American values.” King, a formidable figure in the 1960′s “New Journalism,” died Thursday in a Washington retirement home. He was 83.

“He was in the top caliber of Texas writers like Elmer Kelton and Larry McMurtry” – said Kinky Friedman. “He was one of the funniest people I know. He has been bugled to Jesus. Anytime I use that phrase I swipe it from Larry L. King.”

Lawrence Leo King was born New Year’s Day 1929, in Putnam. He had said his mother wanted him to become a preacher, but she made the mistake of introducing him to the works of Mark Twain, with whom King shared a cutting wit.

King pursued writing in high school and in the Army, following a single year at Texas Tech, before covering crime and sports for newspapers in Midland and Odessa.

In 1954, King shifted from journalism to politics, working with U.S. Reps. J.T. Rutherford and Jim Wright. King’s work during that time informed his 1978 book “Wheeling and Dealing: Confessions of a Capitol Hill Operator.”

After 10 years on the Hill, King left to pursue writing full time, starting with work for the Texas Observer, where he caught the eye of editor Morris. King published his first novel, “The One-Eyed Man,” in 1966.

A year later Morris began publishing his work in Harper’s, where King’s vernacular style and fearless critiques of hypocrites and fools set him apart in the New Journalism vanguard. He seemed particularly drawn to the sorts of people referred to in one of his book titles – “Outlaws, Con Men, Whores, Politicians and Other Artists.”